|

|

Canyon Lake and the Guadalupe River

Early Settlement The earliest European settlements along the Guadalupe were Spanish missions, but none of them survived. In 1726 Franciscan friars moved the Mission Espiritu Santo de Zuniga from Matagorda Bay to a bluff overlooking the Guadalupe near present day Victoria. They tried to build and maintain a dam to divert water from the River to irrigated fields, but they abandoned the effort in 1736. In 1755 and 1756 missions were established at San Marcos and Comal Springs, two locations where large springflows provided a constant source of flow for the Guadalupe, but those missions also failed. In 1808 an attempt by 80 people to construct a permanent settlement near present day Gonzales was defeated by Indian raids and floods. The first successful permanent European settlement took root in 1824, when Martin de Leon received an empresario grant to colonize lands in the lower Guadalupe Valley and founded the city of Victoria. The following year, Green de Witt from Kentucky obtained a grant to settle 400 families and founded the town of Gonzales. By 1850 two other settlements, Seguin and New Braunfels, were also becoming important in the Guadalupe Valley as centers of trade and population. The scenic beauty of the Valley attracted many, and the promise of economic opportunities afforded by the River convinced them to stay. Cattle, cotton, timber, and oil were economic mainstays, and between 1850 and 1900 the population increased ten-fold from 9,300 to over 100,000.

Early Hydropower Development In 1904, Professor T. U. Taylor surveyed the possibilities for development of hydropower in Texas and he classified the Guadalupe River as "the most effective" for this purpose. In 1912, several Guadalupe county residents joined venture capitalists to form the Guadalupe Water Power Company. They acquired a permit, commissioned surveys, and began to purchase river frontage for several lakes and dams to produce electricity. Their work was interrupted by the First World War and slowed by the death of several of the principals, but gained new life in 1924 when Alvin J. Wirtz joined the effort. Wirtz had grown up along the Guadalupe, served as a Texas Senator, and was one of the most prominent citizens and water law attorneys in south Texas. As general counsel for Guadalupe Water Power, Wirtz successfully secured financial backing and completed a deal with the Comal Power Company to purchase all the electricity for their power network. Construction of the $2 million initiative began in 1926 and by April of 1927 three dams between New Braunfels and Seguin created lakes that took up nearly all that stretch of the River. The power plants used water wheels ranging from 1,650 to 2,600 horsepower, with generators averaging 1,400 kilovolt amperes. The Seguin Enterprise described it "one of the foremost hydro-electric enterprises ever pushed forward in all of the Southwest." Before long, the lakes had begun to draw many people for recreation, including camping, fishing, duck hunting, boating, and swimming (Kesselus, 2002).

Flood Control Becomes a Priority Though it presented economic opportunity, the Guadalupe also posed great danger. Frequent floods caused loss of life and property, and preventing them became an increasingly important concern for the residents. A preliminary report that looked at managing the River for navigation, flood control, irrigation, and power generation was completed by the Corps of Engineers in August 1929. It resulted in the authorization of a more comprehensive survey completed in 1933. This report was used by the Corps of Engineers to complete a survey of more than 180 rivers mandated by the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1927, the "308" Report. It recommended construction of a dam that would control floods downstream, regulate streamflow, and provide conservation storage. However, an undertaking of this magnitude was clearly beyond the scope of any individual or private organization. A public organization was needed. So in 1935 the Texas Legislature created the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority and gave it the power to develop, conserve, and protect the waters of the Guadalupe River Basin and to aid in the prevention of damage to persons or property.

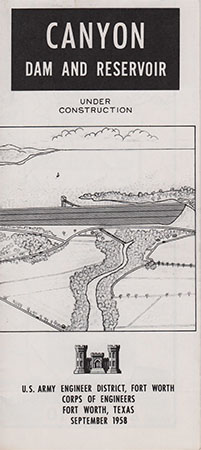

Canyon Dam The site initially identified for Canyon Dam was about five miles upstream from New Braunfels. After the 308 report, additional hydrologic studies were done, and the underlying limestone rock was found to be so honey-combed and porous that engineers had serious concerns about major leakage that could occur. Large losses might make power generation infeasible, so Chief Engineer E. A. Markham recommended additional study and did not recommend the project at that time. The Board of Engineers for Rivers and Harbors rejected the 308 Report recommendations for constructing Canyon Dam. There were major floods in 1936 and 1938, and a group of civic, business, and agricultural leaders formed the Guadalupe-Blanco Basin Improvement Association and started to demand the federal government take action on flood control. The group asked Congress to authorize the Corps of Engineers to reevaluate the Canyon Lake project, and the Corps issued a favorable report that led to Congressional authorization for construction of the Dam in the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1945. The Corps was instructed to prepare a pre-construction report, the Definitive Project Report, which it completed in 1951. The Report recommended moving the dam site about 16 miles upstream, and it also recommended postponing power generation because leakage losses were still projected to account for as much as 25% of total storage. The engineers thought it would be better to wait and see how much water would actually be available for power generation so they could size the generating capacity accordingly. Final approval for construction was given in the Flood Control Act of 1954.

In a letter to the Corps of Engineers in July 1955, the Texas Board of Water Engineers reaffirmed the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority's role as the state agency with whom the Corps of Engineers should negotiate and coordinate the details of construction and operation of Canyon Reservoir. In September 1957 the two agencies formalized their relationship as partners in the project with a contract that allocated costs and operations & maintenance responsibilities. After some funding delays were overcome, construction proceeded and was essentially complete by June 1964. Canyon Dam was finally dedicated on April 20, 1966. The total cost was $20.2 million. Below is a brochure published by the U.S. Army Engineer District in Fort Worth when the Lake was under construction in 1958, and a 24-page promotional newsprint magazine from 1966.

In the ensuing decades, with Canyon Dam in place, recreation and tourism flourished in areas downstream that had previously been subjected to severe floods. Homes, summer cottages, campgrounds, water outfitters, and tubing operations all became commonplace and part of the south Texas culture. However, the Dam has not been able to provide complete protection from floods. In 1972, and again in 1998, intense rains below the Dam site resulted in devastating floods in New Braunfels and areas downstream. In July of 2002, a stubborn low-pressure system parked itself over the region and much of south Texas received almost a year's worth of rainfall in less than a week. Canyon Reservoir filled to capacity and water rushed over the spillway for the first time ever. The southern access road to the Dam was washed out, and more than 800 homes were destroyed or damaged. With the reservoir at record levels, thousands of oak trees dotting the shoreline began to suffer from a lack of oxygen and most did not survive. Discharges from the Dam had to be halted temporarily because of rocks and debris that accumulated around the outlet structure. Residents feared that when releases were initiated again, about 40 homes below the dam would be flooded because rocks and debris that washed down the spillway channel created a "plug" obstructing the Guadalupe's flow about a mile below the Dam. The raging spillway waters created a scenic new gorge, which the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority leased from the Corps of Engineers in October of 2005, with intent to operate the site as a tourist attraction. Guided tours began in October of 2007, and reservations can be made online at http://www.canyongorge.org For more on the history and construction of Canyon Dam, see G. P. Kiel's book "A History of Canyon Dam", published in 1992 by the Guadalupe County Historical Commission, and available at Bookmania in Sattler. For the latest data on Canyon Lake surface elevation and volume in storage, see the USGS Real-Time data page.

The deal with San Antonio. San Antonio had a chance to purchase 30,000 acre-feet per year of surface water from Canyon Lake in 1976, but City Council voted the proposal down. The City is often criticized for having rejected the purchase of Canyon Lake water, and it's easy for people today to point out that if San Antonio had JUST bought that Canyon water back then, it wouldn't have such a problem now. But there's MUCH more to the story, and it is a tale that illustrates the way in which nothing regarding the Edwards Aquifer is clear-cut. Most people tend to see things in yes/no or good/bad terms. It is never this simple with Edwards Aquifer issues There's usually at least two sides to the story and when you hear all the arguments things always end up seeming not so black-and-white. Here is what happened: Back in the 50's when Canyon Lake was being planned by the Corps of Engineers and the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority, the region's most severe drought ever recorded made San Antonio realize it needed to broaden and diversity its water resources and end its complete dependence on the Edwards Aquifer. So San Antonio approached the Corps and GBRA and asked to be included as a partner in the Canyon Lake project. They said no. GBRA has always seen its role to be that of a regional water broker and it did not like the idea of having anyone else involved, especially a partner with a claim to a large chunk of the water. The City filed a lawsuit and GBRA argued in court against inclusion of San Antonio, saying it had a right to act on its own and that in any event, it would be illegal to transfer water to San Antonio because State law said inter-basin transfers of water were not allowed. The matter eventually went to the Texas Supreme Court, and San Antonio lost. The Court upheld a State agency's ruling that San Antonio could not reach outside the boundaries of its own river basin until those resources had been completely developed, and it ruled the Corps and GBRA did not have to let San Antonio be a partner in the project. Since San Antonio had the Edwards Aquifer, which was not being used to its full extent at that time, the Court's opinion was San Antonio therefore did not need surface water. Decades later the same Courts hammered San Antonio for not having planned any alternate or supplemental water supplies, an irony that was not lost on San Antonians. Well, by the mid-70's the GBRA's first annual payment on the project of $308,890 was almost due, and it needed to raise money quick. Cities in the Guadalupe Basin had been reluctant to purchase Canyon Lake water, and the Authority did not have the power to raise revenues through taxes. It had little choice but to offer water to San Antonio. When the proposal to buy Canyon Lake water was floated, lots of people in San Antonio remembered the court battle from 15 years earlier and did not want to purchase water from an agency that had previously rejected their bid to be included as a partner in the project. Also, it seemed a little duplicitous to many that GBRA had argued that transferring water to San Antonio was illegal, but was now willing to do it. And naturally some people said "...wait a minute, I though the Court said we didn't NEED that water!" Aside from those reasons, the people of San Antonio were very proud of the fact their entire municipal supply was wonderful artesian groundwater, and they were very reluctant to mix any surface or treated waters with it. Until August of 2002, San Antonio was the only major U.S city that did not fluoridate water before distribution. They also saw Canyon Lake water as only a drop in the bucket compared to the volumes that planners suggested would be needed, and there was significant oppositon to the idea in the city of New Braunfels. It is clear there were many reasons that San Antonio decided not to buy Canyon Lake water; today most people only remember that it failed to do so and remained dependent on the Edwards Aquifer.

Water Development Projects A recently completed project, the "Western Comal Project", was initiated to supply Canyon Lake water to users in Comal, Bexar, and Kendall counties. The Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority constructed a $39 million treatment plant on Canyon Lake and 43 miles of pipelines to deliver up to 7,000 acre-feet of water per year to users around the lake, seven schools in western Comal county, three water purveyors in the Bulverde area, and the cities of Fair Oaks and Boerne. Increasing the size of the project to also supply some water to Bexar county users makes it more cost-effective. It is a relatively small amount of water, up to 6,000 acre-feet per year, but it represents a significant step for San Antonio in moving away from complete dependence on the Edwards Aquifer. For over 30 years, the GBRA was authorized to sell up to 50,000 acre-feet of water from Canyon Lake per year. In September 1999 the GBRA sought permission from the State to divert 40,000 acre-feet per year of Canyon Lake water from powering hydroelectric dams toward human consumption instead, raising the total it is authorized to sell annually to 90,000 acre-feet. Opponents voiced concern that tubing and fishing, as well as habitat for rare turtles and endangered whooping cranes, could be jeopardized. A plan was worked out that will provide 250 to 350 cubic feet per second, a flow that is believed will sustain the fisheries, recreation, and wildlife habitats. The first draft report of the South Central Texas Regional Planning Group, released in June 2000, recommended diverting up to an additional 50,000 acre-feet of underutilized surface water rights per year from the Guadalupe River at the Saltwater Barrier near the Texas coast. Another 15,000 acre-feet per year could be available from Canyon Lake, along with 20,000 acre-feet per year from the Gulf Coast Aquifer and some additional variable volume from unappropriated streamflows, for an overall total of 94,000 acre-feet per year. The Saltwater Barrier is an inflatable dam constructed in the early 1960's just downstream of the confluence of the San Antonio and Guadalupe rivers, about 3.5 miles north of Tivoli. The dam serves to prevent the up-river intrusion of saltwater and creates a reservoir pool from which water could be pumped. The Planning Group's recommendations include a river intake and pump station, an off-channel dam and reservoir, a reservoir intake and pump station, a raw water pipeline to a treatment plant, a water treatment plant, and distribution systems to municipal users or the recharge zone. Total cost was estimated at around $618 million, with a resulting annual unit cost for water of around $755 per acre-foot. The main environmental issues are ensuring continued adequate freshwater flows to the estuary below the project and potential mitigation for the 1,218 acres that would be inundated by the off-channel reservoir. The Group also studied four additional water supply projects dealing with Canyon Lake and the Guadalupe River that did not make the final list of recommendations. One of these would have been similar to the Saltwater Barrier option, involving diversion of unappropriated streamflows and uncommitted water from Canyon Lake, but the diversion point would be at Gonzales instead of the lower Texas coast. The other three options involved using Guadalupe River water for additional Aquifer recharge. In one option, two potential diversion points below Comal Springs were studied where water could be diverted and then released to streams in the Recharge Zone where it would make its way back into the Aquifer. Another option involved diverting Guadalupe River water in the reach between Comfort and Center Point and pumping it to the watershed divide where it would flow to Medina Lake, and then it would be pumped to the Edwards recharge zone in northeastern Medina and northern Bexar counties. The third option involved diverting floodwaters stored in Canyon Lake to the Edwards Recharge Zone via Cibolo Creek. In March 2001 dozens of elected officials and Canyon Lake residents turned out for a public hearing on the GBRA's proposal to divert an additional 40,000 acre-feet per year from the Lake. Officials from many cities from Boerne to Kyle urged the State to support the plan, while many Canyon Lake residents expressed fears the Lake would be pumped dry and there would be less flow in the Guadalupe River below the dam. Opponents also indicated they didn't want San Antonio to get any water. The plan called for water rights sold to users in Bexar county to eventually be returned to Comal, Guadalupe and Kendall counties when they are needed, but some expressed a belief that once San Antonio got the water, it would be difficult to get it back. On April 23, 2001, the New Braunfels City Council voted to not contest the state permit for the construction of the pipeline for the Western Comal Project. On May 9, 2001, the TNRCC considered the GBRA permit to divert an additional 40,000 acre-feet. People that had been working for and against the project for a long time considered this to be the "moment of truth", when the TNRCC would decide. As it turned out, no decision was made that day. Representatives from Trout Unlimited, a conservation group that has a 40-year history of assisting the Parks and Wildlife Department in managing the fishery below the dam, asked for a contested case hearing. The fishing group expressed fears that during years when the flow from the dam is cut back, the water could get too warm for the non-native fish it stocks there and kill them. Instead of either issuing the permit or acting on the request for a contested hearing, the TNRCC gave the parties until June 20 to try to work out a compromise. No deal was reached and on June 20 the TNRCC granted Trout Unlimited a contested case hearing. However, negotiations continued and on July 17, a deal was reached that allowed GBRA to move forward. GBRA promised to release more water from the dam in years when Canyon Lake is full. Additional releases could be up to 900 acre feet a year, which could serve almost 2,000 families. Release of that volume of water would reduce the Lake level by only 1.2 inches, according to GBRA General Manager Bill West. Officials in Comal county were angered by the deal and threatened to counter with lawsuits and formal objections to the TNRCC. Comal county judge Danny Scheel said "They are putting the life of a fish that is not even native to that river above the health, welfare and well-being of people in a seven county area. We have given our district attorney authority to enter lawsuits against GBRA or Trout Unlimited." Meanwhile, on May 18, 2001, the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority, the San Antonio Water System, and the San Antonio River Authority signed a 50-year agreement to act on the Regional Planning Group's recommendation to divert Guadalupe River water at the Saltwater Barrier near the Texas coast. SAWS was to get up to about 63,000 acre-feet per year and SARA would get up to about 7,000. SAWS President Eugene Habiger said a new treatment plant would ensure customers wouldn't know the difference between Edwards water and Guadalupe water, and that SAWS would distribute the water fairly and would not focus on certain parts of the city getting only certain types of water. In November 2001, the board of the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority authorized its general manager to prepare permit applications for submission to the TNRCC that would enable GBRA to fulfill the contract. In March 2002, the GBRA attempted to quell fears of Canyon Lake residents about new water sales by adopting a resolution saying it would not sell any more water from the Lake without a review and input from local county judges. By March 2002, GBRA had 76,000 acre-feet under contract, and rumors were that GBRA planned to immediately sell their remaining 14,000 acre-feet as soon as their permit was approved. Also in March 2002, in a lawsuit brought against GBRA by Friends of Canyon Lake, a district judge ruled that testimony would be limited only to the question of whether GBRA violated open meetings laws. Friends of Canyon Lake had hoped to air testimony on whether an objective environmental and economic impact study had been performed as part of the permitting process. The group was concerned that selling more water from Canyon Lake would have a drastic effect on Lake levels. On March 18, District Judge Margaret Cooper dismissed the lawsuit with no comment. Friends of Canyon Lake appealed the ruling, but it was upheld by the 3rd Court of Appeals in November 2002. In January of 2003, plans were firmed up to include 20,000 acre-feet per year from the Gulf Coast Aquifer in the project that involved diversions from the Guadalupe River near the Salt Water Barrier. The Boards of SAWS, SARA, and the GBRA all signed letters of intent to lease groundwater from the owners of about 20,000 acres in Refugio county. A group of landowners would receive a payment of about $300,000 per year, increasing by 10% per year for 12 years, and then they would be paid $75 per acre-foot. In February of 2003 a study was released that concluded GBRA's use of an additional 40,000 acre-feet of water from the Lake would enhance the recreational economy and increase the value of lakefront properties. Many Canyon Lake residents feared the opposite. The study was conducted at the request of Comal county and the Friends of Canyon Lake, performed by an independent consultant, and funded by the GBRA. BBC Research and Consulting concluded that overall, there would be more business income, more jobs, more tax revenues, and higher Lake levels with the GBRA permit amendment than without it. After a briefing on the report by the consultant, many Canyon Lake supporters were still mystified about how using more water from the Lake could result in higher Lake levels. The study included an assumption that future Lake levels would be lower because of increased use of existing rights and lower inflows, so it is essentially an analysis of what the impact of the permit amendment would be on the Lake as it is projected to exist in the future. In March of 2003 the Texas Supreme Court dismissed the lawsuit brought by Friends of Canyon Lake, clearing the way for the GBRA to divert additional water from Canyon Lake and sell it to regional municipalities. In July of 2003, the GBRA completed a study that suggested development would threaten the quality of water in Canyon Lake unless Comal county implements rules to reduce the amount of pollutants reaching the Lake. The study recommended a water quality protection zone around the Lake that would require low impact development. It suggested that new rules be implemented limiting runoff and impervious cover. One controversial recommendation was for three new regional zero-discharge sewage treatment facilities, where recycled water would be used for irrigation instead of discharged to watercourses that enter the Lake. Some environmentalists feared that establishing regional treatment plants would encourage more high-density development, since minimum lot sizes would not be required. On the other hand, some suggested that requiring large lots might turn the area into a place for elites only and would likely be struck down by legal challenges. In September of 2003, a study by LBG-Guyton Associates suggested that using the Evangeline Aquifer to drought-proof the plan to divert Guadalupe water from a location near the Saltwater Barrier would have minimal effect. The idea is that if drought interferes with the plan to divert from the Guadalupe, groundwater withdrawals would occur instead. The study suggested that in a worst-case scenario, Aquifer levels would drop almost 80 feet but would recover quickly with rainfall and reduced pumping in wet years. Ranchers in the area said the study was miscalculated and misleading, and that it failed to consider the cumulative impacts of other groundwater projects. Engineers for Guyton said the groundwater availability model on which the study was based was in draft form and that other, as yet unspecified projects, could cause Aquifer levels to drop further than projected. In October of 2003, the Friends of Canyon Lake went back to court in another attempt to stop the GBRA's Western Comal project. This time, the group sued the US Army Corps of Engineers in federal court, alleging the Corps should have performed a full environmental impact statement before letting the GBRA build its new pumping station and pipeline. GBRA General Manager Bill West said "Every court that has heard FOCL's claims has rejected them, and we have no reason to believe the federal courts will be any more receptive to these untrue and misguided charges." By May of 2004, the FOCL had plans to offer the court another reason why the project should not be allowed: shoreline erosion. The FOCL web site said that a senior geologist from a major oil company with a second home at Canyon Lake had carefully surveyed the shoreline structure of the lake and asserted that the delicate limestone-shale-marl stratification is fragile and prone to “slumping,” “sink-holing,” and erosion, particularly when subjected to alternate periods of wetting (expansion) and drying (contraction). GBRA General Manager Bill West said "I don't know who this geologist is, but he just does not know what he is talking about." In September of 2004, U.S. District Judge Royal Ferguson ruled in favor of GBRA and the Corps, setting the project back on track for completion in late 2005. In August of 2004, a terse exchange of letters between SAWS and GBRA brought into question the ability of the two agencies to work together to complete the project to divert Guadalupe River water from near the Saltwater Barrier. Because of lingering acrimony over the Canyon Lake deal in the 1970s and GBRA's intervention in the 1990 lawsuit that eventually limited San Antonio's pumping from the Edwards, their relationship has never been exactly cozy. Bill West cited three bones of contention that he said "are clearly contrary to the spirit" of the agreement and "undermine the partnership and trust that GBRA and SAWS have worked so hard to develop." One was the request by SAWS in July 2004 for a Fish & Wildlife Service review of the science that established minimum flows at Comal and San Marcos springs. Another was SAWS' support for the junior/senior permit system that EAA attempted to implement in May 2004, and the third was SAWS' support for a drought plan proposed by the Edwards Aquifer Authority which did not assure springflows in a repeat of the drought of record. In June of 2005, the San Antonio Water System decided not to pursue participation in the project to pump Guadalupe River water from near the Saltwater Barrier. In the mid 1990's, SAWS established a "shotgun" approach to water planning and began evaluating many different alternatives with the realization that some of them might not prove to be feasible or cost effective, and not all of them would be needed. In early 2005 SAWS President/CEO Dave Chardavoyne formed a task force to evaluate progress on all the potential projects and to consider costs, legislative challenges, environmental concerns, local opposition, changing population projections, and new per capita usage patterns. The task force recommended that San Antonio drop its participation in the project. By October 2005, the GBRA had announced that it would seek new partners, reconfigure the project to drop the groundwater component, and develop the remainder of the project to serve the river authority's statutory 10-county district. In November of 2005, the GBRA signed a letter of interest with a private consortium, Sustainable Water Resources, LLC. The agreement was expected to lead to agreements to supply communities along I-35 north and east of San Antonio. In August of 2008, GBRA officials announced the available water was fully committed. Many cities have reserved much more than they currently use to ensure a supply for future growth. GBRA General Manager Bill West said "With the requests for water we have on the books to date, if you are coming in the door today asking for Canyon Lake water, you are too late." In October of 2008 the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority announced the filing of permit applications for a new "Mid-Basin" water project that would provide up to 30,000 acre-feet of water per year to Caldwell and Hays counties. The plans include drawing water from the Guadalupe River near Gonzales, along with a Carrizo Aquifer wellfield and an off-channel storage reservoir on a tributary of the Guadalupe River. The permit application requested that during wet years, GBRA be allowed to divert all 30,000 acre-feet from the Guadalupe. During dry years, the Carrizo wellfield and/or the off-channel reservoir would supplement available Guadalupe supplies. GBRA General Manager Bill West said he hoped the project could be online in five to seven years. When TCEQ issued a draft permit for the Mid-Basin project in July of 2013, opposition began to mount from environmental groups and other regional water providers. Environmental concerns included the effects on the bay and estuary system and the endangered Whooping Cranes that make their winter home in San Antonio Bay. The San Antonio Water System joined the protest, saying it was not clear what impacts the permit might have on its rights to pump groundwater and also on its recycled water effluents, which provide base flow in the San Antonio River during dry times. The San Antonio and Guadalupe are actually one river system - they confluence just above the coast before reaching the bay. The home of the Whooping Crane, the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, is located adjacent to the point where waters from the Guadalupe/San Antonio river system enter the bay, so use of water from either stem impacts the timing, volume, and quality of water that supports the habitats of the Refuge. In March of 2015, the TCEQ seemed to violate its own rules when it declined to give seafood wholesalers a say in permitting for the project. They believed their business would be affected because it would throw off the delicate freshwater and saltwater mix in San Antonio Bay, harming the oysters, shrimp, and flounder which they market. TCEQ rules say that economic interest is a factor in whether or not the agency should consider a party affected by an application, thus triggering a civil trial-like procedure known as a contested case hearing. In 2020, with the groundwater component of the project already well underway, TCEQ approved the issuance of a new 75,000 acre-foot per year surface water permit. When complete, the project will conjunctively use groundwater, surface water, off-channel storage, and aquifer storage and recovery to manage the entire supply. A Precedent Setting Water Rights Permit Application In 2000, the San Marcos River Foundation, a non-profit group founded in 1985, filed an application with the Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (TNRCC, now TCEQ) for rights to virtually all the remaining unallocated surface waters in the Guadalupe River. Such an application was unpredecented in Texas, and the filing stirred an emotional debate regarding the State's past success and future role in protecting environmental resources. If successful, the SMRF group planned to transfer the rights to the Texas Parks & Wildlife Department and dedicate the waters to instream use, helping to ensure adequate freshwater flows to the coastal bay and estuary system. Approval of such an application would have marked a profound change in the way Texas manages and protects natural resources. Currently, the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ) is the agency charged with protecting the State's natural resources and managing them for sustainable economic development. TCEQ rules consider instream uses to be a recognized 'beneficial use' of surface waters, but in the past the term has generally meant water left in the stream for recreation, navigation, and protection of endangered species. Approval of an application such as the one SMRF filed would have far-reaching implications, because it would transfer publicly held resources to private hands without the understanding the resources are to be used for economic development. They would be used only for environmental protection. Issuance of such a permit for the Guadalupe would essentially mean that no more Guadalupe River water would be available for economic development. Approval of such a permit would also call into question the TCEQ's role as the State's lead environmental agency, since a large portion of the water resources that TCEQ is charged with protecting would no longer be under their control. If the rights are assigned to Texas Parks & Wildlife, they would be under the control of an agency whose mission does not include economic development. The TNRCC ruled the SMRF application administratively complete in December 2000. Partly in response to the SMRF application, the Texas Legislature established the Texas Instream Flows Program (TIFP) in 2001, which directed State agencies to "...conduct studies and analyses to determine appropriate methodologies for determining flow conditions in the state's rivers and streams necessary to support a sound ecological environment." The process was expected to take about 15 years. The statewide goal for Texas rivers is "A resilient, functioning ecosystem characterized by intact, natural processes and a balanced, integrated, and adaptive community of organisms comparable to that of the natural habitat of a region." Taking action on the SMRF permit was on the TCEQ's March 2003 agenda when in February Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst asked the Commission to defer action on the permit until the Texas Legislature could address the issue. He said the law was not clear on whether the TCEQ could issue a permit for the sole purpose of preserving instream flows, and he would ask the Legislature to consider the TCEQ's powers and duties "before a new and far-reaching precedent is set." The announcement was applauded by the GBRA and condemned by representatives of the San Marcos River Foundation. GBRA General Manager Bill West said Dewhurst had put the issue on the right course. SMRF executive director Diane Wassenich said that using the water to maintain the river and estuary would clearly be a beneficial use, which is the guideline the TCEQ uses in assigning water rights. West said he agreed that adequate flows should be ensured, but it should be done by asking the TCEQ to develop rules for environmental permits, not through a permit application such as filed by SMRF. TCEQ commissioners disregarded Dewhurst's suggestion to defer action and on March 19, 2003, they voted unanimously to deny the SMRF permit. The action dealt a stunning blow to SMRF conservationists and other groups who had subsequently filed similar applications for unallocated waters in other Texas river basins. TCEQ Commission Chairman Robert Huston said his research clearly showed his agency has the responsibility to provide for downstream environmental flows. He said "I do not find even a hint in the Water Code that the commission was granted the express authority to grant a stand-alone permit for environmental flows." SMRF attorney Stuart Henry said the action was illegal and he would take the issue to district court. In December of 2003, Lt. Gov. David Dewhurst announced several appointments to a legislative committee charged with examining the issue of whether future legislatures should authorize issuance of environmental flow permits such as that sought by the SMRF. One of the appointments was of Sen. Ken Armbrister, chairman of the Senate Natural Resources Committee, who authored legislation in 2003 that created the study commission. The Commission's final report, issued in October of 2004, offered eight observations regarding flows reserved for environmental purposes. First of all, because of Texas' diversity, a "one size fits all" approach is not correct. Also, the Commission observed that studies would need to focus in detail on the specific relationship between flows and sound ecological environments, and that participation by stakeholders is of paramount importance. It found shortcomings in the State's methods for developing instream flow recommendations, and shortcomings in methods used for determination of freshwater volumes required by the bays and estuaries. It recognized that both regulatory and market strategies would be required, and it stressed that management schemes would need to be adaptive to respond to new scientific knowledge. Finally, the Commission observed that completion of the Texas Instream Flow Studies program would be essential. The lower Guadalupe (below Canyon Dam), was one of the rivers on the Priority List, and a study to determine instream flow requirements was originally scheduled to be completed by 2010. In late 2008, the due date for the Priority studies was moved to 2016, mainly because of funding limitations. The cost for such studies can easily exceed $1 million. Guadalupe: Endangered or Well Protected? In April 2002, a non-profit group that monitors the nation's waterways, American Rivers, ranked the Guadalupe River as the 10th most endangered in the nation. The group said the main threat to the Guadalupe was the State's new water plan, which it says does not place enough importance on conservation and fails to ensure sufficient flow for fish and wildlife, especially in the estuaries along the coast. It also said that GBRA's plans to expand diversions from the Guadalupe posed an immediate threat to the River and its estuaries. The GBRA disputed American Rivers' opinion, saying the Guadalupe is not endangered and is being managed well. GBRA Manager Bill West said the entire regional water plan "is geared around protecting the springs and the River. It is just the complete opposite of what they claim." The Guadalupe-Blanco River Trust The Guadalupe-Blanco River Trust is a nonprofit land trust organization that was developed to conserve land in the Guadalupe River Watershed for its natural, recreational, scenic, historic and productive value. It was founded in 2001 by the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority, a conservation and reclamation district created in 1933 by the Texas Legislature. The Upper Guadalupe River Authority (UGRA) has also partnered with the Trust. The voluntary board of directors consists of citizens who share a love of the Guadalupe River - one of the most pristine rivers in Texas. Ensuring Flows for the Future In 2001 the Texas legislature had a great idea: figure out how much water should be in the River to support a sound ecological environment. In 2007 the Texas legislature had another great idea: figure out how much water should be in the River to support a sound ecological environment. Although these two legislative endeavours have an identical goal, there are some key differences in their approaches, strategies, and scopes. The first program, known as the Texas Instream Flow Program (TIFP), was created under Senate Bill 2 in the 2001 legislative session, and it is also known to river geeks as the SB2 program. The Legislature directed that state agencies would determine flows necessary for a riverine "sound ecological environment“ by conducting extensive field analysis, and that stakeholder input would be considered. It also provided zero funding for the extensive scientific analysis that would be necessary. The second program is known as the Environmental Flows, or E-Flows program, and it was established under Senate Bill 3 in 2007, so it is also know as the SB3 program. Under this program, regional stakeholders are the primary drivers, not the state agencies. The other main difference is the SB3 program includes freshwater inflows to the bays and estuaries, not just instream flows. The Legislature directed that a Stakeholder Committee and an Expert Science Team be created for each major river basin in Texas. The scientists are charged with determining the flows necessary to support a sound ecological environment in both the rivers an bays using the best available science, thereby eliminating having to wait indefinitely for funding and extensive analysis under the SB2 Instream Flows program. They are instructed to make flow recommendations by considering the environment only, not other needs. The SB3 Stakeholder Committee is charged with examining the scientist’s recommendations, then formulating their own recommendations by balancing both human and environmental needs. Both sets of recommendations are then submitted to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), which engages in a rulemaking process, considers input from any interested parties, and promulgates new rules regarding environmental flows that are to applied to any new surface water rights applications. The entire E-Flows process is intended to be iterative and subject to periodic review, so that if new science becomes available under the SB2 Instream Flows program, it can be incorporated into flow recommendations and rules. In the San Antonio/Guadalupe basin, the SB3 E-Flows process started in the fall of 2009 with the appointment of a Stakeholder Committe comprised of representatives from environmental organizations, municipalities, industries, water purveyors, and other interest groups. The Expert Science Team was appointed in the spring of 2010 and conducted an intense one-year evaluation, mostly of existing data, but which did also include much new science. They formulated flow recommendations for 16 gage locations in the San Antonio/Guadalupe basin, along with recommendations on inflows to the bays and estuary system, and submitted their report on March 1, 2011 (get the report here). On September 1, 2011, The SB2 Stakeholder Committee submitted their own report, which included some adjustments to the Science Team recommendations to make allowances for planned water projects and other concerns the stakeholders had (get the report here). The recommended strategies to maintain adequate flows included voluntary set-asides, dedication of wastewater flows, and dry-year options. The Stakeholder Committee was also directed by the Legislature to keep working after their report was submitted and develop a Work Plan for the future, a prioritized list of knowledge gaps and additional studies they felt were needed to improve and refine flow recommendations. Before the SB3 process started, and in light of the state’s failure to fund any SB2 studies, the San Antonio River Authority (SARA) stepped up to the plate and volunteered to fund the extensive studies envisioned in the SB2 Instream Flows program for the San Antonio River. Studies like this take a number of years and involve an incredible amount of fieldwork to scientifically link flow rates and response in aquatic habitats. SARA and their contractors sampled some 12,000 fish under a variety of flow conditions, did habitat and substrate mapping, hydraulic data collection, water quality measurements, riparian zone analysis, and sediment transport studies. The draft flow recommendations and lots of useful data were available to inform the SB3 Science and Stakeholder Committees. Unfortunately, a full-blown SB2 analysis has not been conducted for the Guadalupe, so less information was available. The Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority seemed to be the most likely candidate for funding a complete SB2 study, but it declined to do so. The good news is that almost all the SB3 regional stakeholders agreed on goals for flow in the River and strategies to ensure they occur. Amongst the committee of 25 persons, 28 votes were taken to approve recommendations on flow regimes and other matters, and 17 of these votes were unanimously in favor. In the other 11 votes, no more than 3 votes were cast against. In addition, the scientists and stakeholders generally agreed on things. In other basins where the SB3 process has occurred, there have been major disagreements between and among stakeholders and scientists. In March of 2012, the TCEQ released draft rules which they proposed to publish for public comment in the Texas Register prior to final adoption. Stakeholders were alarmed to find that TCEQ staff had eliminated many of their recommendations. Both the Science Team and the Stakeholder Committee had recommended a full suite of flows that were based on the state’s own scientific guidance documents. These included minimum subsistence flows, a range of seasonal base flows, a tier of pulse flows that occur after rain events, and overbank flows that are important for riparian zone habitat and stream channel morphology. The Stakeholders had also recommended an environmental “set-aside” of 10% for new permit applications. The TCEQ staff proposal eliminated the set-aside, the overbank flows, and most tiers of the base and pulse flows. Changes were more dramatic on the Guadalupe River side of the basin, where the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority has several new off-channel reservoirs planned. When the Stakeholders were struggling to formulatie their recommendations in marathon all-day/half the night sessions, GBRA objected to almost everything; it seemed that if the group desired chocolate donuts, GBRA would demand glazed. At a meeting of TCEQ Commissioners on March 28 to approve the rules for publication, Stakeholders packed the room to urge the Commissioners to instruct that staff revise the proposed rules to more closely reflect the Stakeholder recommendations. Before it was over, the Commissioners had adopted an amendment that left the door open for TCEQ staff to make revisions that would return many of the Stakeholder recommendations to the rules package. After the March 12 hearing, a public comment period followed, and thousands of comments were submitted that mostly support revisions that would more closely mirror the Stakeholder recommendations. On May 25, the Stakeholder Committee completed its Work Plan and submitted it to TCEQ so it would be available during the period that rules might be revised (download the Work Plan here). During this period the TCEQ was invited to one of the final Stakeholder work sessions to make a presentation regarding the proposed rules. Most Stakeholders felt that TCEQ had disregarded their recommendations without any justification, and they were hoping to hear some. They did not - they only heard a reiteration of the proposal. Stakeholders pointed out that TCEQ staff was present at all the Stakeholder meetings, and it could have at least signalled they were recommending things that had little chance of receiving TCEQ approval. TCEQ pointed out the Legislature directed that it "consider" Stakeholder recommendations, not necessarily accept them. Most Stakeholders ended up feeling like they were sort of tricked into spending a lot of time and effort doing something that TCEQ knew all along it was simply going to trash. They felt that TCEQ undermined the Legislature's intent for the process to be mostly Stakeholder driven. After the public hearing and the comment period, the TCEQ staff declined to make any significant changes to their initial proposal. The prevailing opinion among most that are knowledgable about the workings of the water business around here is that TCEQ staff is highly intimidated by GBRA - it appeared that TCEQ simply acquiesced to pressure from that agency. When TCEQ Commissioners met to adopt the new rules on August 8, Commissioner Carlos Rubenstein proposed an amendment to return at least one of the protections to the Guadalupe River, a seasonal high pulse flow, which the great majority of Stakeholders and public comments supported. That amendment was adopted, and the final rules became effective on August 30, 2012 (download them here). In the end, the whole SB3 process left most Stakeholders dissatisfied with both the outcome and the process, questioning whether Texas really has any commitment to protect her rivers and bays.

Senate Bill 2 studies for the Guadalupe In January of 2013, the first public meeting was held regarding the process of conducting in-depth Senate Bill 2 flow studies for the Lower Guadalupe, similar to those already completed for the San Antonio River. The results of these studies could eventually be incorporated into the adaptive management process outlined in Senate Bill 3. At the public meeting in Seguin, agency staffers laid out the process for interested citizens and sought public input on how the studies should proceed. This meeting pointed up a vast cultural divide between residents along the Guadalupe and the San Antonio. At the stakeholder meetings for the San Antonio River in 2009, citizens were mostly interested in maintaining a naturally functioning ecosystem. There was vocal opposition to the San Antonio River Authority's plans for development of recreational venues along the lower San Antonio River. In contrast, recreation was pretty much all the Guadalupe stakeholders wanted to talk about, from trout fishing to tubing to kayaking and swimming. Four breakout groups all reported back that recreation and its associated economic activity were among their highest priorities, and nobody mentioned water supply. It seemed residents were not fully aware the Senate Bill 2 process is focused on determining flows necessary for maintaining a healthy ecosystem, not other uses like recreation or water supply. Those concerns were addressed by stakeholders in the Senate Bill 3 process which, as mentioned above, resulted in adoption of rules in August of 2012 that attempted to balance the needs of both humans and the environment. There was general disappointment, almost an insurrection really, among the attendants about the proposed scope of the Lower Guadalupe study. The study area is defined as beginning in Seguin and ending in Victoria, and it seemed that most of the attendants were from higher up in the basin where no studies are proposed. They were very vocal in advocating for studies above Seguin and they quizzed agency staffers about the omission of that area. It was explained that the line of demarcation is not arbitrary, there are reasons for it. Below Canyon Dam, flows are already managed under the permit for impoundment of water in Canyon Lake. Between New Braunfels and Seguin, the Guadalupe is entirely impounded by a series of dams for hydroelectric power and is not really a free flowing stream. Below Victoria, the river becomes very homogenous without a lot of habitat diversity as it transitions into the coastal marshes and estuary system. This leaves the segment between Seguin and Victoria as a candidate for new exhaustive studies. Intensive flow and habitat studies were actually begun by the agencies in 1997, but the flood of 1998 totally reshaped the River and made all the data collected unusable. After the flood, the agencies did not reinitiate the studies. When Senate Bill 2 established the Instream Flows Program in 2001, the segment beginning at Canyon Dam was designated as a priority study area and at that time the reach from Canyon Lake to New Braunfels appeared on early agency brochures, but that stretch of the River no longer appears as a priority study zone in later publications. Failing Hydroelectric Dams Speaking of hydroelectric dams and free flowing streams, in May of 2019 a gate on an almost 90 year old dam on the Guadalupe that creates Lake Dunlap failed, largely draining the lake. There are many residents and vacation homes on Lake Dunlap that have used the lake for recreation for many decades. On June 5, 2019, about 900 people packed the New Braunfels Convention Center to hear officials from the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority outline options for repairs. All six of GBRA's hydroelectric dams needed to be replaced, at a projected cost of about $180 million. But GBRA doesn't have the money. In an era of cheap power from inexpensive natural gas and deregulation of energy markets, the economics of selling hydroelectric power didn't support the cost of repairs. And GBRA cannot use revenue from water sales and wastewater treatment to fund them. Environmentalists suggested the best option might be to remove the dams and return the Guadalupe to a free flowing stream. But others pointed out the decline in property values and tourist revenue would be significant for landowners. The whole situation raised a number of interesting ethical and environmental issues, such as: Does the public at large have a responsibility to fund repairs that would mainly benefit the landowners? Even if the cost of electricity produced could fund repairs, does a responsibility for environmental stewardship instead demand the dam's removal? These were unanswered questions, but there was talk among landowners of forming a district that would tax landowners based on linear feet of river frontage to fund repairs. The GBRA offered to transfer the Lake Dunlap dam to such a district for $1. But it was not clear if enough money could be raised for repairs, or if it would even be the right thing to do from an environmental perspective. In the end, environmentalists lost the debate about whether the dams should be removed. In 2019, the GBRA board approved pursuing a deal with the newly formed Preserve Lake Dunlap Association that would create a water control and improvement district around the lake. GBRA would borrow money to pay for reconstruction of the dam and gates, and the property owners would be asked to approve a tax to pay the debt. Also, GBRA would contribute all gross revenues from its hydroelectric system at Lake Dunlap to pay for maintaining and operating the dam. TCEQ approved creation of the Lake Dunlap Water Control and Improvement District in February of 2020, and by August of 2020 GBRA reached a similar deal with property owners on Lake McQueeney and Lake Placid. For the Lake Dunlap district, voters approved upper limits on tax rates in November of 2020. Repairs began in 2021 and by September of 2023 the Lake was being refilled. In May of 2024 the Texas Parks and Wildlife Department began restocking the Lake with fish. Some Canyon Lake and Guadalupe River photos

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||