|

|

Conservation The bottom line on residential conservation is that it is cheap and easy, and the water savings are real and immediate. Conservation is our cheapest, quickest source of additional water to support economic growth. The reasons for conserving water and the impact of doing so are a little different in San Antonio than in most places. Lots of places get their water from surface reservoirs and when users conserve, the water remains in the reservoir for later use. In contrast, when users in San Antonio conserve water, all of the water conserved does not remain available for use tomorrow. Some of the water not pumped in San Antonio emerges as springflow at Comal and San Marcos springs. By conserving, users in San Antonio are helping to maintain springflows that are critical for endangered species habitats, recreational economies in New Braunfels and San Marcos, and downstream flows that support industries, cities, and fisheries along the coast. In this way, conservation benefits all of south Texas, which in turn benefits San Antonio, because we are all one economic region. Think about this: almost half of all the water we pump from the Aquifer is used outdoors in the summertime, which is also the time when rain is scarce and springflows are most likely to be low. It's easy to see why almost every summer we get in a "water crunch" and mandatory restrictions have to be imposed to protect the endangered species in the springs and all the uses below. For those who adopt it, conservation is an attitude and a way of life. It is a way that YOU can make a personal statement about being committed to helping the San Antonio region and south Texas ensure adequate water supplies for everybody while continuing to grow economically, and it also shows your concern for the environment and the natural systems we depend on. There are lots of ways to conserve water, and residents of San Antonio have already come a long way. In 1984, each person used about 225 gallons of water per day. In recent years, per capita use has hovered around 115-120 gallons. In its 2017 Water Plan, the San Antonio Water System established a goal of 88 gallons per person day by 2070, and this could vary by 8-11 gallons with impacts from weather.

Even though we impose drought restrictions, it's a mistake to think that San Antonio is "water-poor" and is going to run out of water. We are always going to have enough water for our basic needs. It's the discretional outdoor use that mostly needs to be limited, and it has to do not only with ensuring springflows but also with cost. One of the recent trends that SAWS has noticed is that while overall water use has stayed about the same, the peaks in water demand are higher. This is likely due to the increasing trend of installing automatic sprinkler systems in new homes. In the water business, it's all about meeting the peak demand, and failing to do so is simply not an option. An electric utility can use tools like rolling brown-outs and people are inconvenienced, but having people go without water threatens public health and safety and is just not possible. Now meeting the highest of peak demands is very expensive - a utility has to have everything in place including water supplies, tanks, pumps, and pipes, all to meet the peak demand on a few days a year. It's like having an expensive Lexus convertible parked in your driveway that you only use a few times a year, when most days you can drive your economical Toyota Corolla. This is why many utilities focus so much on outdoor use. Indoor conservation is important as well, but it's that discretionary outdoor use in the summertime that drives peak demands. Consider the chart below, which is water supplied by SAWS each day during the drought year of 2011. Notice the saw-tooth pattern in the peaks that developed in the summertime. This was because outdoor watering was not allowed on weekends, so usage dropped dramatically on Saturdays and Sundays. At the point where all the daily fluctuations end, one could unscientifically draw a line and call everything above the line outdoor discretionary use. This is a large component of total water use and is the most important component in managing the peak demand.

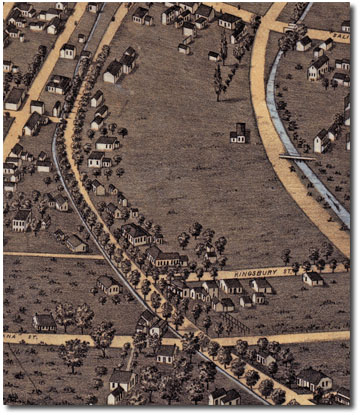

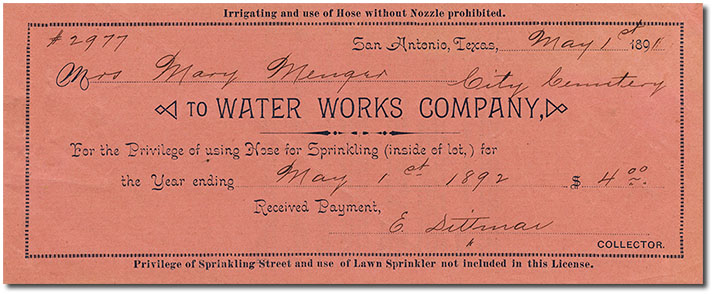

Some Background In January 1997, the San Antonio Water System convened a committee of community representatives to evaluate conservation programs already in place and recommend new ideas. It was a broad coalition of over 200 volunteers representing community groups, neighborhood associations, environmental groups, and business and military institutions. The consensus of the group was the fairest way to get all SAWS customers to conserve water would be to revise the rate structure to allow for lot size, reward water savers, and raise rates for those who waste water. SAWS also began developing an array of conservation programs for just about any aspect of residential, commercial, and industrial use. Today it has more than 25 individual programs tailored to help you conserve in everything from toilet retrofits to swimming pool filters (see SAWS programs). SAWS has earned an international reputation as a leader in conservation and water resource development - foreign visitors come from all over the world to see first-hand what SAWS has accomplished, and utility managers in other U.S. cities also look to SAWS as an example. When SAWS updated its Water Management Plan in 2012, it estimated it could save 16,500 acre-feet per year by 2020 with advanced conservation. This is water that is just as wet as any new water brought from elsewhere, so it counts as a new supply in SAWS' water supply inventory. In the 2017 Plan update, SAWS estimated that by 2070 conservation investments would replace the need for additional water supply projects of approximately 132,000 acre-feet per year. In a lot of ways, the water conservation strategies that San Antonio uses with such success today are simply a return to the past. Take for example the detail below from Augustus Koch's 1873 Bird's Eye View of San Antonio. In those days, San Antonio relied primarily on a system of acequias or aqueducts built by Spanish colonial settlers more than 100 years earlier to divert springflows from San Pedro Creek and the San Antonio River. One of these canals is seen running from top to bottom on the left side of the image. Water use from the canals was governed using a system called the dula, in which the important thing was not amount but time. Irrigators were awarded a standard dula of two days during which they could open the gate from the canal to their fields. Today, modern residents have come full circle as they water their lawns on their designated day. One of the other conservation strategies that San Antonio employs is pricing - with an inverted block-rate structure and drought surcharges, users who demand a lot of water pay extra for it. The use of pricing to promote conservation is also a return to the past. Consider the receipt below issued in 1891 to Mrs. Mary Menger (of the famous Menger Hotel). She paid an extra four dollars for the privilege of using a hose for sprinkling. The back of the receipt contains a long list of restrictions, such as "Suffering hose to run when not in use is strictly prohibited" and "No hose shall be used except when held in the hand; the placing of hose by the use of frames, sticks, crotches of trees, or otherwise, is strictly prohibited."

Saving Water at Home One of the main culprits in high water use households is St. Augustine grass. Other grasses like bermuda and zoysia will turn brown and dormant without water, but St. Augustine will die. It has been widely used in San Antonio for decades because it will grow in the shade, is easy to install, is relatively inexpensive, and it just sort of became a traditional, fashionable grass. Even though San Antonio sits on the edge of the vast Chihuahuan desert, the widespread use of St. Augustine gave the city the appearance of a green oasis throughout the 60s, 70s, and 80s. Today, we are changing the face of the city so that it looks more like a town on the edge of a desert. This will go a long way toward ensuring our future water needs, and it doesn't mean you have to settle for an unattractive landscape. Residents are finding there are many ways to create landscapes that are much more colorful and interesting than plain expanses of green lawn. Xeriscaping and wildscaping are becoming much more popular and can actually increase property values. Xeriscape plants are ones that can survive with little or no water once established, and many are native to the San Antonio area. Wildscaping usually involves mostly native plants, and the landscape is planned with the goal of attracting urban wildlife such as birds and butterflies. These landscapes can even include lots of edible plants! There is plenty of help available to people who want to undertake a xeriscaping or wildscaping project. Free brochures are available at most local nurseries, and the San Antonio Water System offers a wide variety of programs, coupons, and rebates to encourage a culture of water conservation. The Texas Parks & Wildlife Department has some excellent material online about creating Texas Wildscapes and registering your wildscape with the Wildlife Diversity Program as a certified Backyard Wildlife Habitat!

Outside the house, you can also use mulch around trees and plants to slow evaporation, and you can spread compost on turf areas. You can also consider driving a dirty car to be the water-saver's badge of honor! If you have to wash it, you can save water by using a bucket instead of a hose, and make sure you use a nozzle you can turn off when not rinsing. There are also a lot of things that individuals can do to conserve water inside the home: - Repair leaky faucets Saving Water in Agriculture Nationally, about 70% of all the water used in the United States is used in agriculture. There is a large potential for conservation here. There are many ways that farmers can conserve water, and in the Edwards region a portion of the the water saved becomes another "cash crop" which they can sell or lease. They can install high-efficiency sprinkler systems, use drip irrigation instead of sprinklers, use mulch, install devices that measure potential evapotranspiration to get a better handle on irrigation needs, use precision land leveling to improve irrigation efficiency, and plant more water efficient crops. In 2002, the Texas Water Development Board estimated that when one acre-foot of water is used commercially, it produces $335,305 in economic benefits. When that acre-foot is used residentially, it produces $39,514 in benefits. In contrast, an acre-foot of water used in agriculture produces only $121 in benefits. When farmers conserve water, they can not only lower their own costs but that water can then be directed toward a "higher and better use" that has far more economic benefit.

|