|

and Brackenridge Park

|

The San Antonio Springs are located mostly in the Incarnate Word community near Broadway and Hildebrand Avenue. There are several major spring outlets and thousands of small springs extending north into the Olmos Basin, and many still flow during wet times. The largest spring, known as The Blue Hole, and many of the smaller springs are now protected in a nature preserve called the Headwaters Sanctuary, established by the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word in 2006. The Sanctuary consists of several acres surrounding The Blue Hole and about 50 additional acres of urban forest. |

| Water from The Blue Hole (above) issues from a large cavern and is now surrounded by an octagonal concrete and stone wall. Unlike the green shade that characterizes most waters from limestone aquifers, The Blue Hole does indeed sometimes have a blue tinge. After intense rainfalls, the springflows here can become very turbid and cloudy. |

Before Edwards wells were drilled, early explorers and travelers described The Blue Hole as a fountain spring, with water gushing many feet in the air. In 1857, Frederick

Olmsted perceived the entire

discharge of the Springs to come from The Blue Hole and he

described the natural beauty of the site:

...The San Antonio Spring may

be classed as the first water among the gems of the natural

world. The whole river gushes up in one sparkling burst from

the earth. It has all the beautiful accompaniments of a

smaller spring, moss, pebbles, seclusion, sparkling sunbeams,

and dense overhanging luxuriant foliage. The effect is

overpowering. It is beyond your possible conceptions of a

spring. You cannot believe your eyes, and almost shrink from

sudden metamorphosis by invaded nymphdom.

Richard

Everett provided an 1859

description of San Antonio Springs and also San Pedro springs, the other major natural discharge from the Edwards in San Antonio:

Two rivers wind through the

city [San Antonio], flowing from the living springs only a

short distance beyond the suburbs. One, the San Antonio,

boils in a vast volume from a rocky basin, which, environed

by mossy stones and overhanging foliage, seems devised for

the especial dwelling-place of nymphs and naiads. The other,

the San Pedro, runs from a little pond, formed by the

outgushing of five sparkling springs, which bear the same

name. This miniature lake, embowered in a grove of stately

elm and pecan trees, is one of the most beautiful natural

sheets of pure water in the Union - so clear, that even the

delicate roots of the water-lilies and the smallest pebbles

may be distinctly seen.

In the graphic above, only the Blue Hole and another spring on the grounds of the Episcopal Diocese are well-defined orifices. The others appear as patches on the ground that seep large amounts of water during wet times and sometimes appear green when all else is brown. Between the Blue Hole and Olmos Dam, there are literally thousands of small springs that sometimes appear as small openings along the riverbank.

There is no clear consensus on exactly where Olmos Creek ends and the San Antonio River begins. The Blue Hole has traditionally been thought of as the place where the River starts, probably because it is readily observable, and perhaps because many mistakenly believed the entire flow of the River to derive from that single spring. As noted above, Olmsted made that mistaken observation in 1857, and his account was part of a widely read best-selling travelogue that is still consulted by environmental historians.

Tradition and mistakes aside, official sources such as maps by the United States Geological Survey place the dividing line at Olmos Dam. An archaeological survey by Anne Fox in 1979 clearly regarded the area below Olmos Dam as part of the San Antonio River. However, other sources and archaeological reports place the dividing line at Hildebrand Avenue, and others indistinctly identify the start of the San Antonio River as where the Olmos Creek confluences with spring flow. But that begs the question of which confluence they are talking about, and none of them say - there is one confluence where the flow from springs on the Archdiocese complex enters, another where flow from The Blue Hole enters, and a third just below Hildebrand Avenue where flow from at least six springs enters.

If one were to insist on following normal naming conventions for streams, there is even a case to be made that the San Antonio River starts far upstream near Loop 1604 where the drainage channel we call Olmos Creek actually begins. It is certainly unusual to rename a drainage channel in mid-stream as happened here, and it is clearly the result of the drastic change in stream characteristics caused by the contribution of the numerous San Antonio Springs.

The upshot of all this is that many opinions on there the River starts are possible, and all of them can be refuted or supported.

In any case, in keeping with official government maps, I have labeled the stretch of drainage below Olmos Dam as the San Antonio River. If you were to ask me as a scientist, I would say the Dam is the logical hydrologic break point, because above that point there are no significant springs and the stream characteristics change enough to buck normal convention and justify a renaming. But as a local traditionalist, I would join the local chorus and say the River starts at The Blue Hole, just because we say so and tradition is important.

|

Most of the San Antonio River between the Blue Hole and Olmos Dam is completely inaccessible when wet; when dry, many small spring outlets are visible lining both banks (click on picture for a better look). |

|

One of the thousands of small springs that flowed in 1992 when the Aquifer stood at a record high. |

The Olmos Basin and its springs were a place among places for native tribes from near and far. Archaeologists tell us there were many hundreds of occupational episodes involving untold thousands of people. Paleo-Indian projectile points over 11,000 years old have been found, along with burned rock middens and other lithic debris.

Most of the artifacts speak to everyday activities - people who visited or lived here hunted and gathered, built fires, cooked their foods, made tools, and carried out countless other ordinary daily-life activities.

On a social level, this was a gathering place where diverse groups speaking different dialects and languages came together for feasts, special celebrations, courtship, trade, and negotiations.

On a sacred level, it was a place where special rituals took place such as the burial of the dead. In the late 1970s, an excavation carried out in association with renovations of Olmos Dam documented 13 burials including eight adults and five children. Unlike most other burial sites in the region, most of these burials included elaborate grave offerings such as shell ornaments, bone artifacts, and a large number of white-tailed deer antlers (Lukowski, 1988). Today we see these things as unusual objects that came from afar or required special craftsmanship, and we conjecture they must have had great spiritual and personal meanings to those whose loved ones had died.

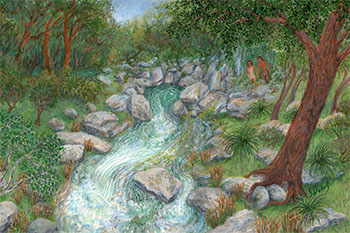

Recently, some ethnographers and archaeologists have offered interpretations of ancient rock art sites in the Lower Pecos region of southwest Texas as portraying elements of native American ceremonial pilgrimages to the peyote fields of south Texas by way of San Antonio Springs. According to archaeologist Carolyn Boyd and members of today's tribes, drawings up to 8,000 years old can be linked to the present day peyote ceremonies of the Huichol Indians of western Mexico.

One interpretation focuses on the White Shaman panel, which natives believe depicts a sacred geography that is south Texas and includes The Blue Hole and three other fountain springs of the Edwards. Natives report that traveling in a circle to 16 springs in central Texas is part of a sacred pilgrimage and a purification ceremony, deeply rooted in native culture and origin myths. The ceremony is a brilliant tradition that ties together water and geography, but also an act of desperation.

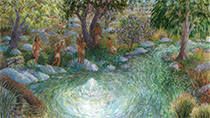

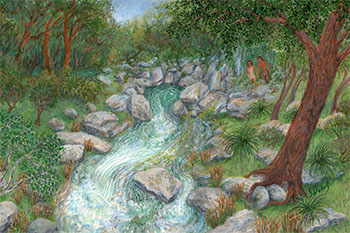

In 2014, artist Susan Dunis created a series of paintings for these pages that depict a family of Lower Pecos natives on this sacred pilgrimage. Each painting illustrates a different aspect of cultural importance of the Edwards springs sites. In this painting, the fourth in the series, the theme is trade. While the ladies enjoy some cool refreshment in the spring we now call The Blue Hole, men are bartering for goods which were painted using excavated artifacts in the Witte Museum collection as references.

|

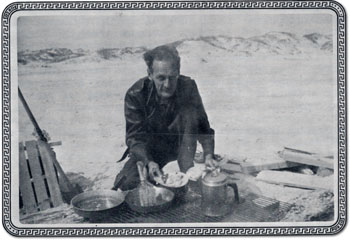

Much of the evidence for prehistoric occupation comes from the work of Charles David Orchard, an avocational archaeologist who worked on the Olmos Dam project and collected artifacts from the Olmos Basin for over 50 years, beginning in the 1920s. He systematically documented his discoveries and also recorded his meetings with transient Indian groups who were still camping there in the late 1920s (Orchard, 1954). He collaborated with various archaeologists and archaeological groups to report some of what he learned and found. |

The story of how life began in San Antonio is beautifully told in mosaic sculpture created by Oscar Alvarado for Yanaguana Gardens, a children's playground in downtown's HemisFair Park. Ramon Vasquez, executive director of the nonprofit American Indians in Texas at the Spanish Colonial Missions, tells the story this way:

A long time, there was a blue panther that lived in a blue hole. One day, a water bird flew into the hole where the panther lived. "And the water bird shot out of the blue hole and opened its wings and the droplets from the blue hole fell across the land, which gave life to the area."

For over 100 years, many historians and scholars believed it likely that Cabeza de Vaca was the first European to encounter the San Antonio Springs in the 1530s. During the nine years that he spent in the region wandering "lost and miserable over many remote lands", he was a trader and faith healer and could apparently travel freely among tribes. However, in his account La Relácion, he never described any springs or terrain resembling the Balcones Escarpment or Edwards Plateau. Some have suggested he passed through the area while making his exit in 1535 to the colonized lands of New Spain, but recent research has provided strong support for the notion that most of de Vaca's escape route from Texas was through Mexico, not Central Texas (Chipman, 1987 and Olson et al, 1997).

The first Europeans known to have visited the Springs were members of a 1691 expedition led by Domingo Terán de los Rios and Father Damian Massanet. On June 13 of that year they pitched camp alongside a group of friendly Payaya Indians at the River's headwaters. It happened to be the day of Saint Anthony of Padua, and they named the spot San Antonio de Padua.

The area came to be known as the Head of the River, and it was apparently an important route in and out of San Antonio. Sketch maps by David Orchard show a deeply worn old buffalo trail that descended into the Olmos Basin near the east end of the dam, and the Camino Real from Mexico to east Texas entered San Antonio here (Stothert, 1989).

Camp of the Lipans by Theodore Gentilz, 1840's

One of the earliest known

descriptions of the Indians who fished and hunted in the area was

written in 1716 by Franciscan missionary Fray Antonio de San

Buenaventura:

They dress

themselves in tanned deerskins, and the women the same,

although they are covered to the feet.

The men spend little concern on their dress, as some of them

go about naked.

They take part in mitotes, or dances, when they wish to go to

war or when they have attained some victory over their

enemies. They do this dance as if gripped by the hands by

which they suffer various abuses, and these dances are causes

of the murders which they commit on each other...

Their languages are different; only by means of signs are

they understood among all the nations. They are governed, and

conduct their trade, with signs.

Their customs are generally the same. Some are more spirited

than others. They are very warlike among themselves, and they

kill one another with ease, for things of little consequence,

as they steal horses or women from each other.

Yet their presence is agreeable. They are of smiling

countenance and are accommodating to the padres and

Spaniards. When they come to their rancherieas they freely

give them what they have to eat.

They are very fond of Spanish dress. Soldiers often give them

a hat, cloak, trousers, or other garment in pay for the work

they do....

Learning is easy for them, and they acquire use of the

Spanish language with facility.

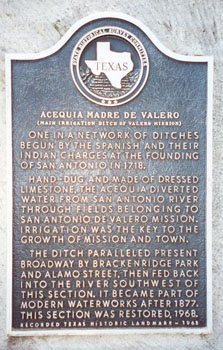

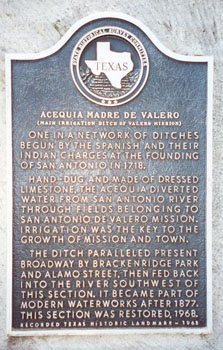

After the Spanish established missions in Bexar, they quickly set about devising an irrigation and water supply system using spring water. The first canal dug at the San Antonio Springs was the Alamo Madre in 1745, and it diverted water from the east side of the headwaters just below the Springs, in present-day Brackenridge Park. Until 1761 the Spanish missions utilized Spring water exclusively for all purposes. In that year a well was dug at the Alamo as a precautionary measure against having access to the river cut off by hostile Indians. Around 1776 a dam was built to divert springflows into a second canal, the Upper Labor ditch, which formed an interconnection with San Pedro Springs.

By the late 18th century, the Olmos Basin was surveyed and most tracts passed from Spanish to Anglo ownership. During the period of the Texas Republic (1836-1845), the headwaters area was still wild and uninhabited, and there was considerable fear of Comanche Indians, who frequently staged raids into San Antonio and surrounding settlements. In her memoirs, Mary Maverick provided a description of some adventurous young couples who took a joyride into hostile territory:

...ladies and all were armed with pistols and Bowie knives. I rode with this party and some others around the Head of the San Antonio River. We galloped up the west side, and paused at and above the head of the river long enough to view admire the lovely valley of the San Antonio. The leaves had mostly fallen from the trees, and left the view open to the Missions below town. We galloped home, down the east side, and doubted not that Indians watched us from the heavy timbers of the river bottom (Green, 1921).

Conflicts with Indians and fears of a Mexican re-invasion of Texas brought soldiers to town, and the headwaters was a preferred camping area. William F. Wilson and his men camped here in 1839 (Pierce, 1969), and in 1840 William C. Cooke established "Camp Cooke" at San Antonio Springs and positioned some of his 1,200 men there (Dunn, 1975). In the mid 1840s another camp, Camp Olmos, was home to local mounted militia and Texas Rangers attached to the U.S. Army under General Zachary Taylor, who were preparing for war with Mexico. In 1849, some of the troops that had fought with William Jennings Worth in Mexico camped around springs in San Antonio during a cholera epidemic in which Worth and 600 others died. The campsite came to be known as "Worth's Spring", possibly referring to what many believe is the large spring at the northeast end of Olmos Dam (see the FAQ on Worth's Spring).

In 1840 an immigrant's guide to the new Republic of Texas advertised that:

Avoca is the name of a new town, laid out at the head springs of the San Antonio River. The position of the town, the chrystalline and cool waters and the scenery, are declared to be beyond anything known, even in Texas (Press, 1840).

Avoca was a dream of William E. Howth, who settled in Texas in 1830 and received two-thirds of a league from the President of the Republic of Texas in 1838 as his "headright." He was an active San Antonio businessman who bought and subdivided many properties as developments. A 1936 newspaper article reported the town of Avoca was a forerunner of Alamo Heights, was founded in 1830 by "a small band of American settlers who found life in San Antonio burdened with the older Spanish settlers here at that time", and that Howth may have led the exodus. The article said that according to local tradition, Avoca was "a very select residential neighborhood, that also had a clubhouse, where historic persons frequently visited." However, a 1972 article questioned the 1930 establishment date and asserted that most of Avoca was on the present-day Incarnate Word College property, with only a small portion in Alamo Heights. Since two-thirds of a league is a very large area, and there are records of land transactions mentioning Avoca that stretch from Milam and Travis streets to downtown San Antonio, the true location has proven difficult to pin down. Whether or not Avoca was actually occuped by a small group of Anglos escaping the Hispanic backdrop of San Antonio has not been conclusively determined (Furman, 1978).

|

In this early 20th century photo, military cadets Willard and Guy Simpson are climbing on ruins near the Olmos Dam that local legend says were one of the earliest houses in Avoca. |

By 1850, San Antonio had declared that its boundaries extended as far as the headwaters of the San Antonio River, and Howth's headright was revoked. In 1852 the city encountered financial difficulty and sold the property to J.R. Sweet, himself a city alderman, for $1,475. The transaction was described by Dunn (1975):

...the City of San Antonio at public auction sold a quantity of land that had been marked off in lots on the Giraud survey map of the same year. Lots 30 and 31 at the Head of the River (in Range 1, District 2) went to Alderman James R. Sweet. City Engineer Giraud urged the city not to sell this property, since Lot 31 allegedly embraced "the North Springs," the main source of San Antonio's water supply. Two years later Sweet was reimbursed $85 of his purchase price because Lot 31 did not contain the springs. In the meantime, however, in 1853 Sweet had purchased Lot 32 on the north side of his property, apparently acquiring the springs in this transaction. When he mortgaged the three lots in 1858 they were described as "Situated at the San Antonio Spring at the head of the San Antonio River".

Sweet built a stone house on Lot 31, now part of the Incarnate Word grounds, and it became known as the "Old Sweet Place." By 1859 his holdings grew to include five other lots for a total of 108 acres. In 1869 the entire acreage was sold to Isabella H. Brackenridge, mother of George W. Brackenridge, for $4,500.

Shortly after Brackenridge's purchase, the question of who should own the Head of the River became a controversial and emotional one. George W. Brackenridge was also a civic leader and philanthropist, and he believed the city should own the Springs. They had become contaminated by outhouses and garbage, typhoid fever and malaria were rampant in San Antonio, and there was a developing awareness of the link between sanitation and disease. The year 1866 brought a devestating cholera epidemic, and the community realized it desperately needed a method of water distribution that would eliminate the possibility of contamination. Many schemes were advanced, discussed and discarded. Brackenridge offered 217 acres, including the Sweet property and adjoining acreage that he owned, to the city for $50,000, providing the city would "never again sell the headwaters." In 1873, while Brackenridge's proposal was in negotiations, a definitive attempt to organize a company and build a water works was made by George M. Maverick, but it failed. Brackenridge's proposal was abandoned in November 1874, after almost three years of negotiations, because the parties could not reconcile the sale price. Another attempt to organize a water works was made in 1875 by H. B. Adams, but it too failed (McLean, 1924).

Finally, in 1877, the city gave a contract to J. B. LaCoste and his associates for supplying the city with water from the Head of the River. The San Antonio Water Supply Company built a raceway and a pumphouse on Brackenridge's property a half-mile below the Blue Hole, and a reservoir was constructed near the western end of Mahncke Park. Water falling from the end of the raceway had sufficient force to operate a large turbine which was connected to plunger pumps, forcing water uphill to the reservoir, where it was distributed by gravity to taps in people's yards (at that time, there was no indoor plumbing). The pumphouse is still standing in Brackenridge Park.

|

Pumphouse #1 was built by the San Antonio Water Supply Company to move springflows to a reservoir near the western end of Mahncke Park. In January of 2018, the San Antonio Conservancy Society pledged $300,000 in funds for repairs and restoration of the structure. The restoration project is also backed by $880,000 in 2017 city bond funds. Plans have not yet been developed, but possible uses might be as a venue for food service or gatherings. |

|

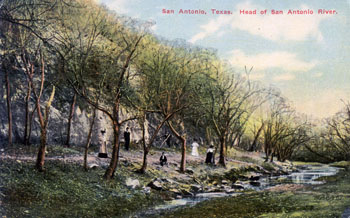

A view of the Head of the River from about the time the first pumphouse was constructed. The image appeared in the San Antonio Guide and West Texas Directory for 1877, by Garza & McKernan Publishers of San Antonio. The only examples of this book I have seen are all marked 'Sample Copy', which suggests perhaps the book was never actually published and only a few copies were made as a marketing tool. From the surrounding terrain, it seems likely this is the discharge of the Blue Hole. |

Whereas the Water Works developers had expected hundreds of people to sign up for service, the number was in the tens, and they disposed of their unprofitable assets to George W. Brackenridge in 1883. Under his direction and foresight, the struggling Water Works Company was built into a valuable property. By 1885, Brackenridge foresaw the possibility of the original plant being insufficient to meet the city's growing needs, and he purchased property along the River about a mile downstream where he built a second raceway and pumping plant to move spring waters to the reservoir. In 1877 he constructed a second reservoir of much larger capacity where the Botanical Center is located today.

|

Pumphouse #2, also known as the Borglum House, still stands near the Brackenridge Park Golf Course clubhouse and has been nicely restored. After it was no longer used for pumping water, it was used for a time as an art studio. It is called the Borglum House because world famous sculptor Gutzon Borglum used it as his studio for 12 years - he completed his design and castings for Mount Rushmore here. |

|

|

A map from 1908 showing the locations of both pumphouses, the long raceway from the River to pumphouse #2, and the two reservoirs. |

In 1886 Brackenridge built a large three-story addition to the Sweet house that became known as Brackenridge Villa, and he called his estate Fernridge. This was a play on words involving his name, because "bracken" is a type of fern. In 1890, William Corner's guide book to San Antonio declared:

...without doubt one of the

most beautiful, if not the most beautiful, places in Texas,

its woodland grace and parklike beauty so heightened by the

perpetual mystery of its profound and noble springs. This is

the Head of the River. There are other fine properties in

this neighborhood with exceptional water advantages and

privileges, but this property was really the key to the

situation, the Ojo de Agua, the birthright of the

city (Corner, 1890).

|

Brackenridge Villa overlooks The Blue Hole and is now home to the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate Word. |

In 1888, from his observations of the wildly fluctuating springflows, Brackenridge became convinced there was danger of complete failure of the Springs as a source of supply. In 1891, he drilled large artesian wells into the Edwards Aquifer, the first large Edwards wells for municipal supply, and springflows became much less important as a water supply source.

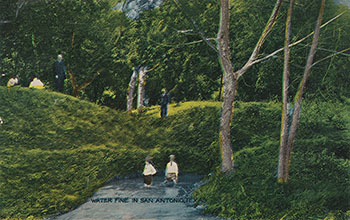

In the Gay 90s, the area around the headwaters was best known as a park. A small dam was constructed, creating a wide and very long lake that was San Antonio's favorite Sunday afternoon rest spot. Francis Huff (1946) wrote:

The gayest memories of Alamo Heights in the 90s and the early 1900s seem to be associated with the park and lake at the Head of the River. A small rock dam had been thrown across the stream, which made a lake where the Halff barns now [1946] are. It reached from the 'big spring' to a point above the present dam, and was a hundred or so feet wide, and two or three feet in depth. Boating and picnicking - especially by moonlight - were favorite sports. It is interesting by the way to see pictures of lovely young girls capably negotiating the steep drop to the lakeside park in their frilly summer dresses. The "Head of the River' was San Antonio's Sunday-afternoon vacation land.

By the late

1890's, flows at San Antonio Springs had been drastically reduced by the drilling of numerous additional Edwards wells and a long drought. Brackenridge could not watch it happen, nor do anything about it, so he determined to dispose of his property. He wrote:

This river is my child, and it is dying and I cannot stay to see its last gasps. It is probably caused by the sinking of many artesian wells. I have paid thousands of dollars for legal opinions on the question of stopping boring of the wells, but they all say I have no remedy - and I must go (Williams, 1921).

Brackenridge sold 280 acres including the

San Antonio Springs to the Sisters of Charity of the Incarnate

Word for $120,000, and in 1899 his Water Works Company donated 343.73 acres of land for

the establishment of Brackenridge Park.

|

A group of young girls boating on campus near The Blue Hole, circa 1907. |

|

|

|

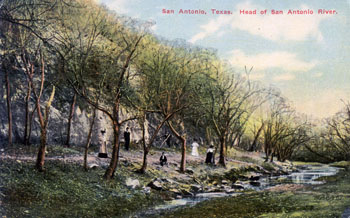

This very rare postcard mailed in 1910 shows that flows at the Head of the River had been drastically reduced from prior decades when the site was San Antonio's Sunday-afternoon vacation land.

History failed to record what Fred Alter was expecting. On the back of the card, he wrote to his mother:

"Nothing doing" yet. Got fooled some way. Have expected it every day since the first. All as well as can be expected. Cold wave predicted for tonight. Funeral with 62 rigs just passed - pretty long. See you later. |

|

|

|

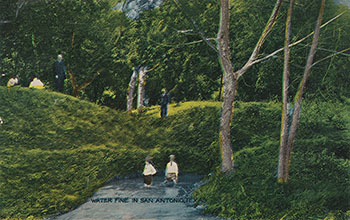

This postcard mailed in 1913 appears to show the stream channel just downstream of the Blue Hole. |

|

|

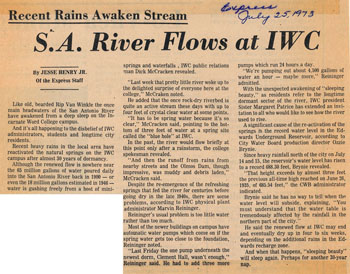

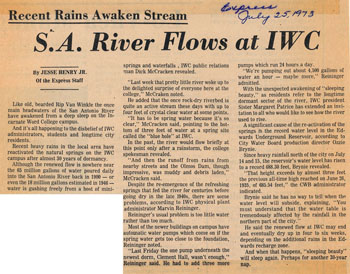

Brackenridge was right in his

predictions about the headwaters. Due to increasing withdrawals

from the Edwards Aquifer, springflows became intermittent and meager. By the early 1940s, the springs had entered a dormancy that lasted 30 years. In 1973, after months of drenching rains, excited news reports detailed how "the city's Sleeping Beauty, otherwise known as the San Antonio River, woke up" (San Antonio Light, July 25, 1977). Many San Antonians got their first look at the outflows that were so important to San Antonio's first 200 years:

|

Like old, bearded Rip Van Winkle the once main headwaters of the San Antonio River have awakened from a deep sleep on the Incarnate Word College campus. And it's all happening to the disbelief of IWC administrators, students and longtime city residents. "Last week that pretty little river woke up to the delighted surprise of everyone here at the college," said public relations man Dick McCracken. |

The newspapers asked residents to send in their remembrances of the old days when numerous springs flowed in the San Antonio River and Olmos Creek, and Seguin resident Lena Dittmar Buerger responded:

My father, the late Herman Dittmar, was engineer for Col. Brackenridge. We lived in the park near the upper pump. My father used to take us to a big spring in back of Incarnate Word College that was known as 'the blue hole.' He had to measure the depth of the water and we were always warned not to go too near because it was bottomless. Whenever there was a fire in San Antonio, a very large bell on our front porch rang. Then one of us - father if he was there, mother or one of us kids - would take a telescope and watch the water level in the reservoir on Government Hill. If it fell to a certain level, we had to start the auxiliary pumps.

Today, none of the San Antonio Springs flow except during periods of extreme rainfall. The River is

kept alive mostly by discharges

of recycled water in Brackenridge Park, and by one artesian Edwards well inside the San Antonio Zoo.

The Head of the River is still the home of the University of the Incarnate Word, managed by the Congregation of the Sisters of Charity. In 2008 they formed The Headwaters Coalition, a non-profit, sponsored ministry dedicated to spreading an ecological ethic and protecting one of the last undeveloped forests in San Antonio, 53 acres adjoining Olmos Creek, including the Blue Hole.

The Blue Hole is still revered as sacred. Dave Orchard reported that native peoples conducted ceremonies involving the placement of precious objects near the Springs or in the Springs themselves, and that tradition continues to this day.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

This is The Blue

Hole, described by early explorers and travelers as a "fountain spring", gushing water many feet in the air. John Russell Bartlett described this chasm in 1850:

The water

rises in a cavity some six or eight feet in diameter and

twelve or fifteen feet deep, and rushes out in an immense

volume. The water of these springs unite with Olmos

Creek, forming a river. |

The Blue Hole on June 14, 1992, the day the Aquifer stood at its recorded high level of

703.3 feet, as measured by the J17 index well. On that record-setting day, The Blue Hole was a long way from being a "fountain spring". Discharge was still only a tiny fraction of what it must have been

when Everett and Olmsted wrote their 19th century descriptions. Notice that you can see several feet below the surface to where the concrete wall ends.

|

|

|

During very rainy times, springs pop up all over the Incarnate Word campus, such as these two appearing from under pavement. The Blue Hole is immediately behind the fence in the background of the photo on the left. The photos were taken in the summer of 2007 after long, intense rains. |

|

|

In 1915 Mrs. Koehler, widow of Pearl Brewery owner Otto Koehler, donated an 11-acre tract between the quarry and the San Antonio River to the City for a public park. San Antonians have never really considered it separate from Brackenridge Park, since they are adjacent and it's difficult to tell where one starts and the other ends. Hildebrand Ave. is the bridge in the background, where a flow augmentation well was located for many decades (see photo below).

|

|

|

A circa 1910 postcard with a boat on the River in Koehler Park, also known as The Lily Pond. |

|

|

In 1996, archaeologists uncovered

remnants of the Spanish colonial dam at the swimming hole that diverted water to the Upper Labor acequia. The dam

was built around 1776 to divert

springwaters and streamflow from the San Antonio River to the acequia to irrigate San Antonio's early farmlands. In the photo at

right the head of the canal is in the upper right corner. The dam was re-covered and there was a picnic table over it for many years afterwards. |

|

|

In 2013, archaeologists discovered the entire Upper Labor dam is still intact. The cut stone blocks at the top were added later by German stonemasons and the original Spanish Colonial construction is seen here beneath them. |

|

|

For many decades, the entire dry-weather flow of the San

Antonio River was derived from Edwards wells in Brackenridge

Park and the San Antonio Zoo. This one was directly underneath the Hildebrand Ave. bridge, at the top of the pond pictured above. In June of 2000, the San Antonio Water System began discharging recycled water in Brackenridge Park so several Edwards well could be cut off, thereby conserving Edwards supplies and helping maintain springflows at Comal and San Marcos Springs. Although unused, this old well leaked when artesian pressure was high, so it was plugged in July of 2008. |

|

|

The Hildebrand well on the day it was plugged in July of 2008. I sort of wanted to write my name in the wet concrete but I did not.

|

|

|

This

well just east of Lambert Beach in Brackenridge Park was also shut off when the flow of recycled water to the River began in June 2000. It is now enclosed in a building and maintained in working order in case there is an emergency need to release water to the River. There is a third well in the San Antonio Zoo, the Hippo Well, that still flows because potable Edwards water is needed for the hippos and other animals. The Hippo Well historically contributed about three million gallons per day to flow in the San Antonio River, but in recent years water usage at the Zoo has come under scrutiny and flow from the well has been reduced by about half. In 2013 the Zoo pumped about 1.6 million gallons per day. |

|

|

The bed of the San Antonio River as it usually looks. This photo was

taken just a short distance downstream from The Blue Hole. The Olmos Basin in which the City of San Antonio grew up

probably had as many springs as any place in the world. They are all

almost always dry now, except during extremely wet years when they

reassert themselves and flow up through the slabs of buildings and into

basements. |

|

|

The winter absence of tree foliage reveals the confluence of Olmos Creek and flows from The Blue Hole in February of '92, an especially wet time when many of the Springs flowed

again. Flows from Olmos Creek are entering from the left. Notice the distinctly bluer shade of flows from The Blue Hole on the right of the channel where the two flows have not yet mixed.

|

|

|

Flows from San Antonio Springs can sometimes be very turbid and cloudy, such as seen here in the summer of 2007 when the Aquifer almost reached a record high. |

|

|

When it was taken in 1991, this photo represented the discharge of several Edwards wells in Brackenridge Park used to maintain flow in the downtown San Antonio River Walk. Today, most of the dry-weather flow of the River here is recycled water from the San Antonio Water System's Dos Rios plant |

|

|

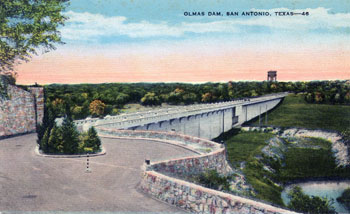

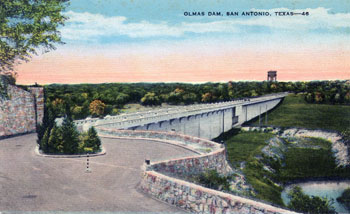

An old postcard showing another view of the Olmos Dam, about a mile above San Antonio Springs. It was constructed after a series of disastrous floods in 1917-1921 took many lives and caused widespread devastation in downtown San Antonio. Construction mostly destroyed what was probably the largest and most important Native American campground in Bexar county. |

|

|

This is the confluence of San Pedro Creek (entering from the left) and the

San Antonio River, the two streams vividly described by Richard Everett in

1859. Photo by William Hudson |

|

|

|

|

| This is a remnant of the

Acequia Madre canal in Hemisfair Park. The canal was used to divert San

Antonio Spring water to agricultural fields belonging to the Alamo. |

Historical marker at the

canal. |

Cathedral Springs are part of the San Antonio Springs complex and are located just off Torcido Drive at the Bishop Jones Center. The 19-acre property was once owned by San Antonio businessman Godcheaux Halff, who founded WOAI radio, and are now owned by the Episcopal Diocese of West Texas. One large spring occurs adjacent to Torcido Drive and another moderately large spring emanates just to the south.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The spring adjacent to Torcido Drive flows profusely when Edwards levels are high enough and rivals The Blue Hole in size. |

Another moderately large occurs just to the south and is surrounded by stacked rocks, which might have made for a swimming hole at one time. |

Godcheaux Halff built a mission-style home on the bluff just above Cathedral Springs and in 1928 he installed a pump to use springflows, when available, and flow from an adjacent Edwards well to water extensive and lush landscaping on the grounds. A rock dam, still standing, created a pool of water to pump from.

The pump was made by the Goulds Pump Company of New York and is one of the few remaining pumps of its era still found in its original installation. Most of these pumps, known as “triple plunger pumps”, were powered by steam, but this one received a state-of-the-art installation and was electrically driven. A motor turned a large belt-driven flywheel, which was connected to a gear drive that slowly moved plungers up and down to displace water.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The small rock dam built by Godcheaux Halff to create a small pool from which to pump and water the ground's extensive and lush landsaping. |

The Halff pumphouse was restored in 2015 and the pump was left in its original condition. The photo is from before the restoration was complete. |

The home built by Godcheaux Halff overlooking the Springs was refurbished by the Episcopal Diocese into a conference center that can accommodate up to about 30 people. There's a full-service kitchen and the bedrooms were left intact. Halff's living room was converted into a small chapel, and the bedrooms can be used as prep and waiting areas for wedding ceremonies.

In 2019, Susan Dunis created a sixth painting in her Springs series for me to commemorate a very special occasion. The theme of this one is romance, and two young lovers are seen approaching the Springs hand in hand. It is not clear who is leading who. I got married in the chapel above the springs on July 20, 2019.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The sixth painting created for me by Susan Dunis in her Springs series. Halff's home, now a conference center and chapel, is on the bluff just above. |

Gregg's wedding day, July 20, 2019. It was the 50th anniversary of the moon landing and the groom's cake was the Apollo 11 capsule. |

|

|

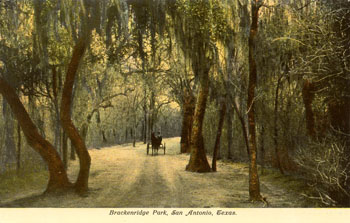

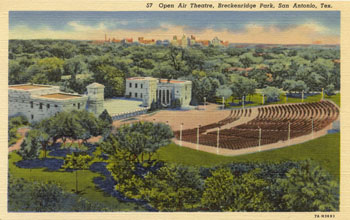

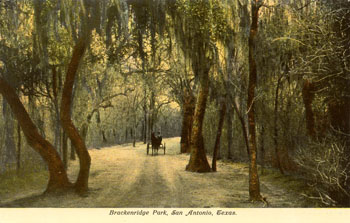

After George W. Brackenridge's donation of land to create the park, one of the first improvements was a series of drives totaling seven miles, designed by Parks Commissioner Ludwig Mahncke. Many postcards depicting the drives were produced, attesting to their popularity as a leisure destination. |

|

|

Cruising Brackenridge Park was a tradition that continued until the 1974 gas crisis. After that, cruising as a recreational activity never really made a comeback. |

|

|

Another of the drives shown in an early postcard. |

|

|

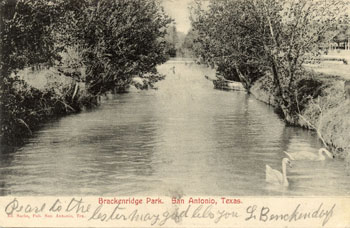

Mailed on Feb. 7, 1907 to Mrs. A. J. Broomhall in Troy, Ohio. |

|

|

Never mailed. |

|

|

By 1902, there was a fenced deer preserve and enclosures for buffalo and elk. Animals were pastured along River Avenue near today’s Lions Field, and were fed with hay raised in an adjacent pasture. |

|

|

The sender must have been an incurable romantic. On Sep. 8 he wrote to Miss Louise Karath in Joliet, Illinois:

These are dear but you see they are not the right kind. You know there is only one kind for me. With love, G |

|

|

The buffalo herd in Brackenridge Park. |

|

|

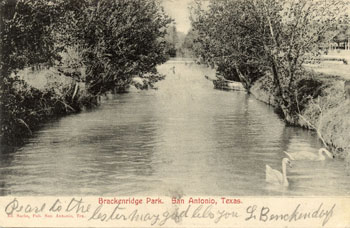

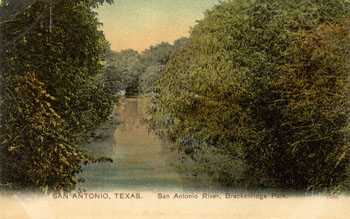

A nice view of the San Antonio River in Brackenridge Park, mailed in 1911. |

|

|

Not mailed or dated, but typical of the Divided Back Era of postcards that lasted from 1907 until 1915. |

|

|

For a long time this section of the Park was known as Lambert Beach, named after San Antonio's first Parks Commissioner Ray Lambert. He built the city's first public swimming pool in 1915 by scooping mud from the River, laying gravel, and calling it a "swimming beach." |

|

|

It looks like there was more socializing than swimming at Lambert's Beach. |

|

|

An ultra-rare Real Photo version of the colored card above. |

|

|

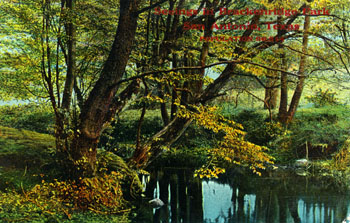

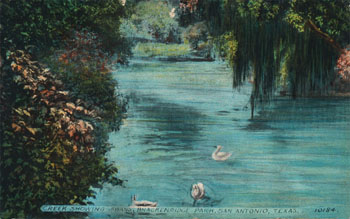

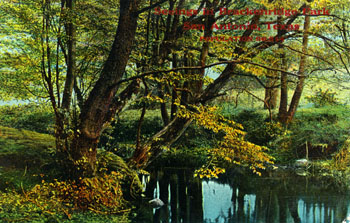

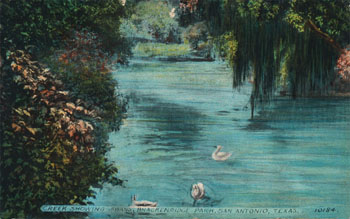

The Dahrooge Company misspelled the Park's name in this view of the swans, circa 1915. The swans were a popular attraction and appear in many postcards. |

|

|

A tranquil scene in the Park around 1920. |

|

|

A colorful view of the River in Brackenridge Park, never mailed. |

|

|

Featuring the ever-popular swans. Mailed on November 9, 1906. |

|

|

The same Real Photo base image as above, this time very nicely hand colored. |

|

|

A nice hand-colored German made postcard, never mailed. |

|

|

Mailed on April 26, 1911 to Miss Emma Kopjolin in Cibolo, Texas, the back of the postcard says:

Dear Emma: I don't know if I answered your last postal or not. Was you in town for the carnival? I had a pretty nice time at the carnival. Give my love to Eva. Love from Ella.

The 'carnival' probably refers to San Antonio's week-long Fiesta celebration, held during the latter part of April each year.

|

|

|

Like I said, the swans were a very popular subject. |

|

|

Yet another card featuring swans, mailed in 1915. |

|

|

Published by Paul Ebers in San Antonio and never mailed. Probably produced around 1920. The caption on the back says:

One of the seclusive spots which, with the lovers' lane, is known best to all park visitors.

|

|

|

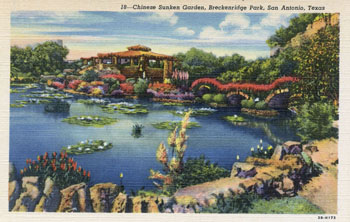

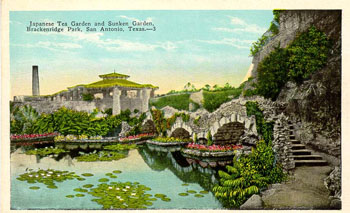

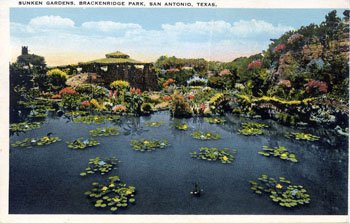

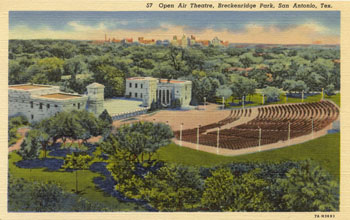

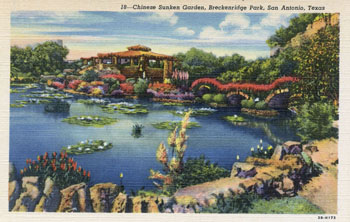

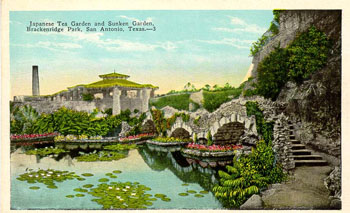

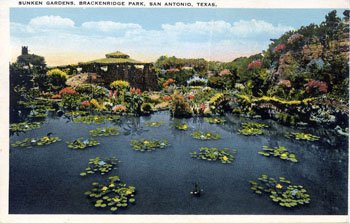

Ray Lambert succeeded Ludwig Mahncke as Parks Commissioner, and his greatest dream was to convert an abandoned quarry on the western edge of the park into a lily pond. In 1917, he set out to accomplish his goal using prison labor and meager resources. Local residents donated exotic plants, and the "Japanese Garden" as the area was called, was hailed in national publications as a unique attraction.

In 2008 the Sunken Gardens reopened after a long hiatus. Volunteers worked thousands of hours to restore the Gardens to their former splendor. |

|

|

The caption on the back says:

The Sunken Garden in

Brackenridge Park is one of the show places of America. It

was an old abandoned rock quarry, but man and nature have

made of it a beautiful sight. A tea garden, managed by expert

Japanese, is situated at the Garden so the visitor may

refresh himself and view the beauties of the Garden at the

same time.

|

|

|

In the 1960s, my family made several trips to San Antonio to visit family. The Sunken Gardens was considered a "must do". The caption on the back of the card says:

One of the prettiest sights in San Antonio. Visited by thousands of tourists annually.

|

|

|

This view of the pagoda was a very popular one. The back of the postcard says:

The Sunken Garden in

Brackenridge Park is one of the show places of America. It

was an old abandoned rock quarry, but man and nature have

made of it a beautiful sight. A tea garden, managed by expert

Japanese, is situated at the Garden so the visitor may

refresh himself and view the beauties of the Garden at the

same time.

|

|

|

Yet another view of the same scene by a fourth publisher. The caption says:

The Sunken Garden in

Brackenridge Park can be reached over the Alpine Drive. Here one can see the Lily Pool, Japanese Tea Gardens and many varieties of flowers. This park was donated to the city by Col. George Brackenridge and contains 363 acres. It has Public Playgrounds, a Golf Course, Bathing Beach, Tennis Courts, a Zoological Gardens and many other things.

|

|

|

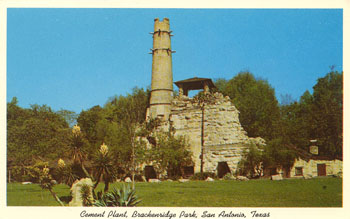

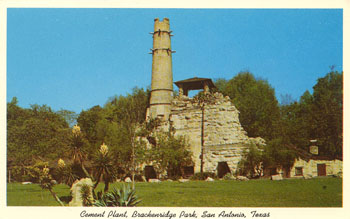

A mid-1960s view of the ruins of the cement plant. It's no longer possible to photograph the same view today because tall trees now obscure the view. |

|

|

Up until the 1960s one could take a "Thrilling motorboat ride in the San Antonio River in beautiful Brackenridge Park near the famous San Antonio Zoo." |

At one end of Brackenridge Park is the San Antonio Zoo, one of the nation's finest. It houses more than 3,500 animals representing 600 species. Over a dozen exhibits cover 53 acres.

|

|

The San Antonio Zoo relies on water from this large Edwards well. It is used to supply about three million gallons of water per day and forms a river that runs through many of the exhibits. |

|

|

The well water flows through an astounding number and variety of exhibits that are home to hundreds of species. |

|

|

Edwards well water is used in the Cliffside Grottos, a habitat for cats of the world that was a gift from the Robert J. and Helen C. Kleberg Foundation. |

|

|

In 2008 the Zoo opened the Africa Live! exhibit, where visitors are immersed in a setting that represents Africa three months after the seasonal rains. The theme of the exhibit is the importance of water in both abundance and scarcity, and visitors are encouraged to make comparisons to places like San Antonio, where it seems we are either water-rich or water-poor all the time.

|

|